From multiplex urban fingerprints to bicycle network planning

📬 Get the future posts directly in your inbox:

UPDATE: The article has been published in Royal Society Open Science

We all know that in some cities it is easier to move using a combination of mobility systems, than in others, but how does the cities enable this options, what are the change possibilities between cities, and more important, can we detect similar cities based on their mobility options?

To answer this and other questions, I’m working together with Federico Battiston, Michael Szell, and Gerardo Iñiguez, in a research project that characterize the city’s mobility infrastructure as a multiplex network, composed of a set of network layers, from pedestrian footpaths and bicycle paths to streets and public transit infrastructure, which enable different modes of transportation.

One of the simplest features of single layer networks is the degree distribution, however, in multiplex networks a node can have different degrees in each layer, in cities, this property provides clues to the multimodal potential of a city. If a city has nodes that are mainly active in one layer but not in others, there is no potential for multimodality. On the contrary, in a multimodal city we expect to find node that are connected in different layers serving as transport hubs, such as train stations with bicycle and street access.

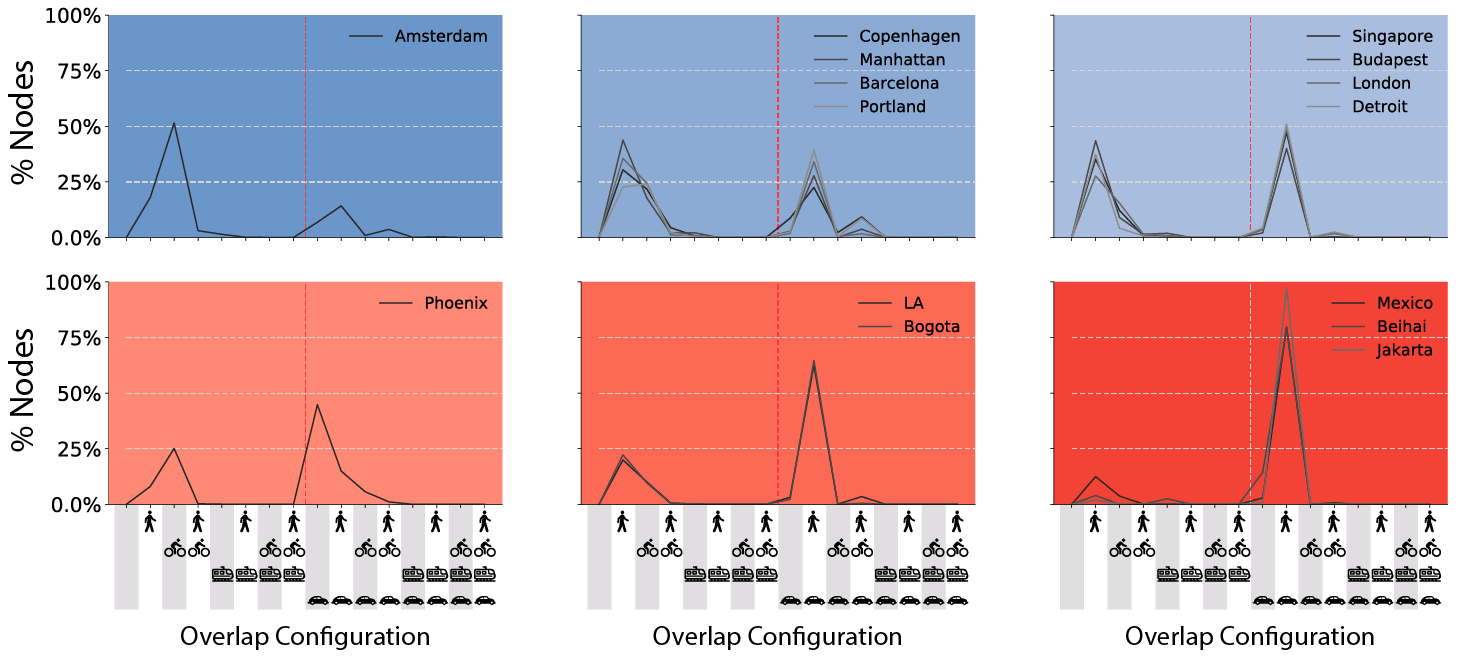

To measure the multimodality we developed the overlap census of a city, a unique “multiplex urban finger print” of multimodality. This approach let us capture the percentage of nodes that are active in different multiplex configurations. Helping us to learn how much focus a city puts on connecting different transportation modes.

We build the overlap census for fifteen different cities in the world, and cluster them together based on similarity of their overlap census. We find six different clusters using a k-means algorithm (coloured areas). Detecting similar cities across the world. We see how some cities like Amsterdam, Barcelona, Portland have the majority of the nodes active in configurations in which the car is not active, while others like Phoenix, Mexico, and Beihai, have the majority of their nodes concentrated in car-active configurations.

In a further inspection of the different layers and configurations of the network, we found that the nodes not only can be active or not in different layers, but also, whit-in the same layer they all can be connected into one single component or fragmented in multiple components. Take the cases of Copenhagen and London, both European cities, clustered in the multimodality ones, however, Copenhagen bicycle layer is composed of +300 different connected components, while London’s is made of more than 3,000 components. This fragmentation in the bicycle layer propose a new challenge, How can we consolidate them into one giant bikeable component? Which is the most optimal way, and how much the bike layer improves?

Our approach is to develop algorithms that find the most important missing links in the bicycle layer, improving its connectivity, bikeable kilometers and the bicycle-car directness, a measure that answer the question “how direct are the average routes of bicycles compared to cars?” The following video shows the implementation of one of these algorithms in Budapest and the improvement of fraction of bikeable kilometers in the largest component. This is what is the fraction of kilometers that we can bike without stepping down of the bicycle infrastructure.

We keep investigating the effects and benefits of following an algorithmic approach to improve the bicycle layer in the multiplex mobility system. Our preliminary results indicates that with a small, focalized investment it is possible to have a great impact, making the point to grow and build the bicycle network, planning in a macro scale considering and connecting first the existing bicycle infrastructure, instead of randomly adding bicycle infrastructure.

📬 Get the blog posts directly in your inbox:

💬 Join the conversation:

Keep to conversation with a comment or reach out in my social networks.